We are living in a world where the truth no longer holds any sway in the pursuit and consolidation of power.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the sordid beginnings of Donald Trump’s America: in the run up to the election the lies were so blatant that it seemed impossible that anyone could take them seriously, but they were dismissed in the name of political rhetoric.

Now that he has taken the reins of the presidency, these lies have become an accepted technique amongst those heading up his regime. There are his tweets, of course – dismissed all too easily as the ravings of a lunatic – but these are given brazen validation by the claims of his team. Sean Spicer insisting that Trump’s embarrassingly small inauguration crowd was the biggest ever seen. Kellyanne Conway inventing a massacre to terrify people into accepting their draconian travel bans.

These outright lies are bad enough on their own, but when combined with accusations of fake news levelled at those who disagree, and the patronising, scathing delivery with which Trumps and his allies address their critics, this segues neatly into classic gaslighting – and gaslighting on a global scale.

Too many people I know – liberals, intellectuals, people concerned with truth as a foundation for society – are beginning to doubt their sanity. It seems almost impossible to believe that people in such positions of power can lie so brazenly and not get called out for it. This is, of course, part of the point – and is something which has been explored at length in publications as diverse as The Washington Post and Teen Vogue.

Something that I’m not sure people are admitting quite so openly is the extent to which this is happening on this side of the pond too. We all raged at the lies printed on the sides of buses during the Brexit campaign. We all shook our heads in disbelief as Michael Gove dismissed the opinions of experts, repeatedly calling into question the very value of expertise. Doctors rallied against Jeremy Hunt over the false statistics he used to support his calls for a seven day NHS. And then this week, when Jeremy Corbyn is still being hauled over the coals over his decision to whip his party into going against their instincts and vote in favour of leaving the EU, Theresa May sends a letter to the electorate in the run up to a crucial by election lying about both Labour’s clearly stated intentions and the voting behaviour of local Labour MPs.

Increasingly, as in the disunited states of America, our politicians refuse to acknowledge these untruths even when presented with incontrovertible evidence to the contrary. And even if they do, the damage has already been done.

The media, with its almost entirely right-leaning benefactors, whips up these lies into something bigger than themselves, and our democracy is left gasping for breath at the heart of it with no-one knowing what to believe any more.

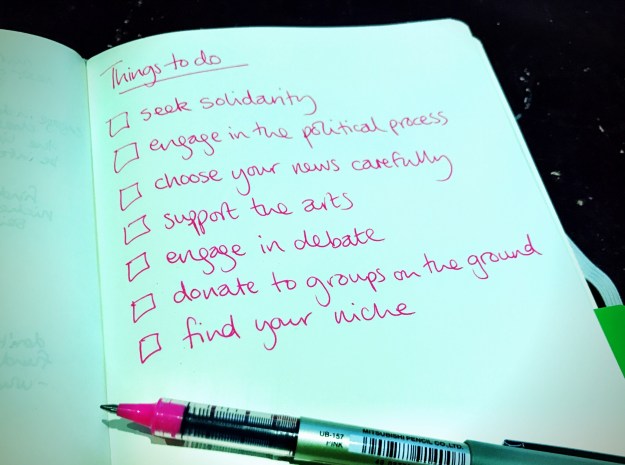

Increasingly an ability to analyse the media and move beyond the role of unquestioning consumer is a vital skill – and yet Media Studies continues to be sidelined and ridiculed. The internet provides us with almost endless news sources, yet at both ends of the political spectrum these twist and subvert the truth: even if you want to question the status quo, to seek out some sort of integrity at the heart of it all, it is all too easy to get dragged down someone else’s rabbit hole.

And actually the reality of the direction our education system – and thus our society – is taking could not be further from harnessing that ability to question and challenge. Our childrens’ minds are being suffocated with pointless facts, their teachers’ creativity and professionalism stifled with the relentless drive of ever-increasing ‘standards’. Schools themselves are in very real danger of becoming nothing more than factories which churn out young people chastised into obedience and so desperate to carve out their own little place in the world that they will sacrifice all their dreams of a better world in order to do so.

We owe our children more than this.

We have to give our young people – our society – the tools to survive, morally and intellectually, in this post-truth world.

Of course this is not in the interests of those in power. As parents we need to act, to show the young people in our care that they are valued, they are important – and they are powerful.

So much of what is accepted – expected – in modern parenting is about championing compliance above all else. We need to fuel the fire in our children’s bellies, give them the strength and the confidence to be active members of society, and above all move away from the idea that it is by being ‘good’, and by doing what we say, that they are most valued, most loved.

It is pretty clear that, however much it might be painful to accept, our generation is not doing such a great job at building a society that we are happy to live in. I’d like to think, though, with thoughtfulness and care, that there is hope our children might.