There are many moments that have stayed with me from my ten years of teaching. The overwhelming majority of them are positive, but there is one in particular that has been circling around my head the past few days that makes me feel so sad about what current government policy is doing to our children’s experience of learning.

Early on in the first term of Year Seven, I often broached the question to my English class “What makes good writing?”. It’s a big question, and not one I ever expected to hear answered in its entirety, but still the responses that I got were pretty telling. The particular set of responses I remember was from Autumn 2012, just before I disappeared on maternity leave. Fresh from SATs preparation, hands shot up as I wrote the question on the board, and the answers spilled out proudly into the classroom: “varied sentence starters”, “correct use of conjunctions”, “fronted adverbial clauses”, “using semi-colons”.

Now none of this is strictly wrong, of course – and I dutifully noted each response on the whiteboard before mooting my own ideas. But it was still incredibly deflating to hear it from a room full of eleven year olds. Where was the talk of imagination? Of storytelling? Of creativity? Where was the space for them to fly?

It is this reduction of learning to rote mechanics that worries me most about the SATs, because the world doesn’t work like that – and yet in order for children to be able to succeed in these exams they have to be trained as if it does. When Key Stage 3 SATs were still around, I remember as an English department poring over questions trying to work out what it was they were actually getting at, and then teaching our students which right answers to put down for which type of question to make sure they got the marks they deserved. It was a preposterous waste of time and energy at a delicate stage in young people’s lives when the cocktail of hormones they were dealing with made the conventions of school pretty challenging anyway.

Still, I can get the argument that (at least within the limitations of our current system) being able to ‘do’ exams is kind of necessary. And I can just about stomach the concept of putting thirteen year olds through that process – at least we could explain to them the whole idea of the hoops they had to jump through, and begin to separate out different types of learning so that the experience didn’t completely extinguish the fire within.

I find it harder to justify for ten year olds, and I think it is such a crushing shame that children’s final year in primary school, a period in education which for many has been characterised by creativity and imagination, is reduced to drills and mock exams and learning ‘right’ answers to the most complex of questions making reopening the door to the potential for real learning a dauntingly challenging task in the years that follow.

Except of course primary school isn’t really like that any more. Not since the reintroduction of KS1 SATs, where children as young as six are now expected to sit formal tests in spelling, punctuation, grammar, reading, arithmetic and reasoning. SIX! The notion of what constitutes correct answers is, from what I have seen, just as convoluted as it was in KS3 – and so drilling is, if teachers are not going to sacrifice the children in their charge (and themselves) on the pyre of government assessment, inevitable.

And then of course there is the question of what all of this drilling occurs at the expense of. Play, for example, and creativity. Various other government initiatives are squeezing out the arts as children move up through the school system, but it is beyond belief that they should be marginalised at this crucial early stage. It goes against all of the research, the experience and the professional instinct that should guide our education system. When I admit that as a result of the regressive nature of government reforms I am reluctant to enrol my child in nursery, friends are quick to defend the relative freedoms that are still enjoyed in the early years. They go quiet when we get on to what starts to happen in year one.

All of this is part of why I am no longer teaching, and is a major driver in my decision to home-educate my son – for the first few years at least. My approach as a teacher always meant that there was a degree of rallying against the system – I wanted to see my students grow as individuals, to try to find creative ways of managing assessment that did not compromise their own personal development. During the bulk of my career, it felt at least as if I was moving with the tide – that what I innovated with one year I could integrate the next as Labour education policy responded to the needs of teachers and schools. And then the Tories came to power.

I could still be fighting the battle from the inside – I have untold respect and admiration for my former colleagues that are – but it is just so exhausting to have to make your classroom a fortress against the outside world, and I have a family to think about now.

My son is three: he is curious, brave, funny, unique and creative. He has many subjects he is passionate about, and is developing his own clear preferences for how he likes to learn about them. I want to nurture those in him, to enable him to find his way through the world in a way that it keeps its wonder, and where he gets to cherish his uniqueness, not play it down to fit in within the system and win validation for himself, his teachers and his school.

These KS1 SATs don’t give children levels; they don’t take a formative approach to identifying their strengths and areas for development; they don’t recognise that each and every child will progress in different areas at a different pace: they just indicate whether they have reached the required standard, whether they have passed or failed, whether or not they are ‘good enough’ at this stage in their lives.

I cannot imagine putting my little boy through that in three years time.

And it looks like I am not alone.

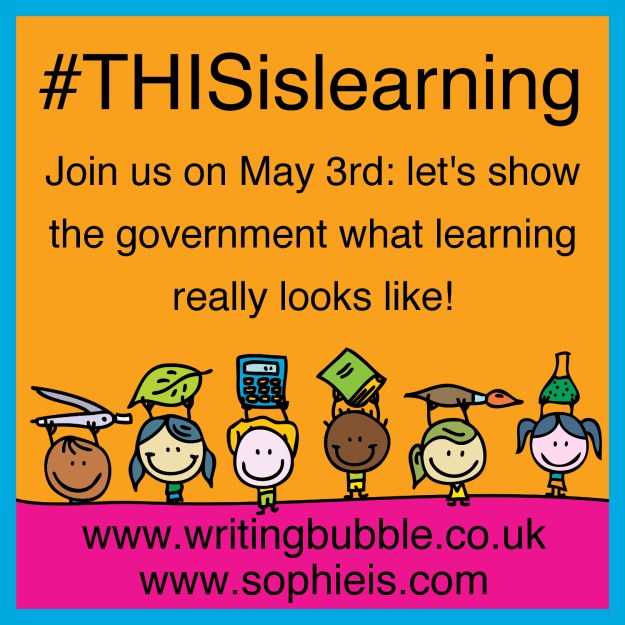

A campaign is gathering pace to undermine the KS1 SATs with a children’s strike on the 3rd of May. Yet more parents are calling for a boycott of the KS2 SATs, where the expected standards have risen so sharply that children are being set up to fail more than ever before. Parents up and down the country are uniting to say that this dismantling of their children’s childhood is simply not OK, that to stop their kid’s learning in its tracks by subjecting it to meaningless assessment is not something they want to be a part of.

My son is too young for me to be able to make a stand in this way, but I will be taking the opportunity on that day to demonstrate just what learning can look like when we set it free: to tell the story of our learning journey on this blog and on social media, to show how much fits into a day when it is not constrained by the need to learn to jump through hoops.

If you too are angry about what current government policy is doing to our schools, teachers and most importantly our children, then I hope that you will join me.

Edited 16th April 2016:

In response to our general disbelief at the way the government are decimating our education system, myself and Maddy from Writing Bubble have started a campaign to show them what learning really looks like.

To find out more, check out our launch post and join our Facebook group. It would be awesome to have you on board.